Escape to victory

Léon Rubin's wartime story, told to Michael Whitburn and Andrée Ferrant, reads like a film script. His account, which first appeared in the branch newsletter in January 2017, tells of his daring escape from the German occupation in Belgium. Encouraged by the Resistance and travelling under an assumed British name, 'Fred Kirkup', Léon made a long and perilous journey via France and Spain, where he was briefly jailed, to Gibraltar.

Securing a passage on a convoy to Britain, he was lucky to make it in one piece after the ships were attacked by German planes. Instead of being welcomed on arrival, he found himself put under interrogation for days. After finally convincing his hosts that he wasn't a spy, he enlisted in the Royal Air Force. A dramatic meeting followed with the widow of the man whose name he used during his escape, before he won his wings in Canada. Léon later returned to civilian life and served as an auxiliary in the Belgian Air Force, rising to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel Aviateur. He passed away on 16 June 2023, aged 97.

This is Léon's story, in his own words.

“When Belgium was invaded In May 1940, I decided to join the Free Belgian forces in England even though I was officially a Swiss national by my father. The trouble was I was only 15 at the time and still at school in Brussels. I had no money, no contacts and no knowledge of English.

It would be nearly three years before I was finally able to put my plan into practice. I had in the meantime managed to save what I believed would be enough for the long and perilous journey through occupied and Vichy France, Franco’s Spain and, via Gibraltar, to England.

I had also spent many hours learning the language with the help of an Assimil textbook and gramophone records, and after two years of studying I felt reasonably confident about my level of English.

Léon and Rayky on their wedding day

I escaped from from occupied Belgium on 14 December 1942. The first part of the journey through France to the border with Spain took longer than anticipated, but everything proceeded more or less according to plan.

I was put I touch with a local “passeur” (people smuggler) whose job it was to take me over the border to Figueras. In actual fact he took me no further than within sight of the town, gave me the name and address of a contact (both of which would later prove false) and then left me to fend for myself. It took me many hours to complete the journey, but I finally arrived, still on foot, famished and looking pretty ragged.

I’m British!

Hardly had I set foot in Figueras than I was stopped by the Guardia Civil and asked to produce some kind of identification. I had none to show them, but told them in my Assimil English that my name was Fred Kirkup, that I was a British citizen who had luckily escaped imprisonment in France and that I wished to be handed over to the local British Consular Service, whereupon I was promptly taken to the local police station and jailed in an overcrowded and smelly cell.

I was finally set free in February thanks to the mediation of a British Consular Officer. Though the British representative was not taken in by my claims of British citizenship, he confirmed everything I had told the Spanish police and made sure I was set free. He took me to Barcelona where I was provided with new clothes, given a false certificate of British nationality and told I could move about at will. I was questioned on a number of occasions and asked to give a great many details about my life history.

After Barcelona, the next stop was Madrid where I arrived escorted by a Consular Officer and where I was again questioned about my past life history. From Madrid I travelled to Gibraltar where I was able to join the Belgian forces. I left Gibraltar on 7 April 1943 on a ship in a convoy of some 30 or 40 vessels heading for England.

Under attack

The journey at sea was a dangerous one and on several occasions the convoy came under attack by German fighter planes before we finally docked at Liverpool.

From Liverpool, immigrants like myself were immediately taken by train to London and the London Reception Centre in The Royal Victoria Patriotic Building, Fitzhugh Grove off Trinity Road.

For several days we underwent tough and intense questioning by highly experienced interrogators.

Once they were satisfied I was telling the truth, I was issued with a document granting “permission to land at London” and told to report to the Belgian Embassy at Eaton Square.

Being a Swiss citizen I was referred to the Swiss Embassy at Montague Square where I was informed that my father had been moving heaven and earth to find his missing son. I was told I would be sent back to Switzerland which, I bluntly told them, I would refuse. Finally, my parents were informed of the situation and agreed to emancipate me.

PM’s support

I was later told Hubert Pierlot, the Prime Minister of the Belgian government in exile, had insisted I be granted permission to join the Belgian section of the Royal Air Force. I joined the RAF on 15 September 1943. The six-week training programme (ITW, for Initial Training Wing) was at Scarborough, North Yorkshire. It was designed to improve discipline, physical fitness and mental alertness and provide a sound basic knowledge of the air force.

The syllabus included armament, engines, hygiene and sanitation, RAF law and discipline, mathematics, meteorology, navigation, flight and signals and, for immigrants like myself, English.

On 22 March 1944 I was then sent to complete my training programme in Canada at North Battleford, Saskatchewan, and received my wings on 2 March 1945 – just two months before the end of the war in Europe!”

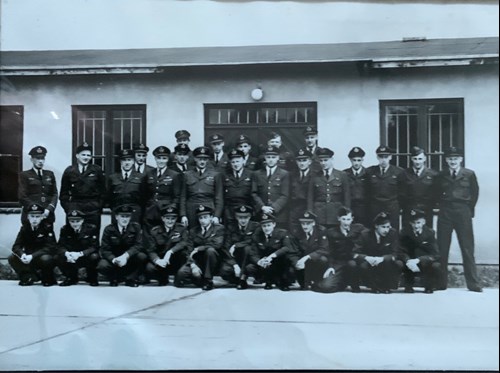

Léon (fourth from left centre row) after receiving his RAF

wings in Canada. He finished first on his course

The Kirkup connection

Soon after Léon’s interview was published, newsletter coordinator Michael Whitburn received a mail from branch member Paul Claes, who was intrigued by the name under which Léon had chosen to travel – Fred Kirkup – during his long and perilous journey to England through France, Spain, and Gibraltar.

It turned out that Paul had two distant cousins in England named Michael and Philip Kirkup, and since it was far from being a common name, he wondered whether there could possibly be a connection between Léon‘s alias and the family in England.

Mails were exchanged between Paul and Léon, and it became clear that there was indeed a connection.

Here, in a sequel to Léon’s interview, is the story of what can only be described as a series of remarkable coincidences:

Léon first thought of using the name Kirkup shortly before leaving the country, following a conversation with Georgette Dieu, a long-standing friend of the Rubin family, who also worked as an accountant for the watch business of Léon’s father.

It was no secret to Léon that Georgette was involved with the Resistance. Léon also knew that Georgette had a close friend in Britain married to an Englishman. Her friend’s name was Lily Wittewronghel. But it was only when Léon told Georgette about his plan to join the Free Belgian Forces that she provided him with details concerning her friend (sadly, Georgette was later betrayed to the Gestapo and deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp where, against all odds, she survived. The person who had betrayed her was executed by the Resistance).

Lily had married Kenneth Kirkup in Brussels on 5 October 1935 and the couple managed to escape to England with their two young sons, Michael and Philip, at the start of the war. They made it out on the last Royal Navy escorted ship before Antwerp was closed. They settled in the North West of England.

Léon felt the name Kirkup had a good ring to it and as an alias it sounded more genuine than Smith or Stephenson. And so it was that Léon decided to call himself Fred Kirkup, son of John and Margaret Kirkup, from Crosthwaite, a village near Kendal in Cumbria.

Meeting Lily

Months later, after he had arrived in England and was attending a military training course at Scarborough, Léon arranged to pay Lily Kirkup a visit at her Lake District home in Windermere, where she was living with Michael, aged six, and Philip, four.

At the time, Lily‘s husband, Kenneth, who was serving as Leading Seaman in the Royal Navy, had been reported missing in action and Lily had been told that he had died in a submarine, somewhere off the coast of Japan (much later it transpired that he had died in the raid on St. Nazaire on 28 March 1942 and that his body was sadly never recovered).

Several months before he contacted Lily, the information about Léon’s nom de guerre was cross-checked by the British authorities for security reasons and Lily had been contacted and asked if she knew anyone by the name of Fred Kirkup.

The mere mention of her husband’s name was enough to give Lily new hope that he was still alive. So when Léon finally got in touch with her, Lily was understandably upset with Léon for having used Fred‘s name and giving her false hope.

The resentment soon disappeared once Léon had told her the whole story and a warm and friendly relationship soon developed between him and the Kirkup family. Towards the end of the war, when Léon was sent to Canada to complete his pilot training, he received a good luck telegram from Lily and her two sons with the words: ―OUR THOUGHTS ARE WITH YOU. LILY MICHAEL PHILIP.

After the war

Léon was demobbed on 4 February 1946 and decided it was his duty to follow in his Swiss father Armand’s footsteps and train in the watch business. After three years in Switzerland he returned to Belgium to work as a commercial agent for Tissot and, later, Émile Pequignet.

But Léon couldn’t give up planes entirely. After acquiring Belgian citizenship, he served as a squadron auxiliary in the air force from 1949 to 1957, ending his military career with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel Aviateur.

Léon (third from left) with Belgian Air Force auxiliary pilots

And it was thanks to flying that he would meet his wife-to-be, Rayky, at an aviation ball. He would always remember the date – 3 March 1951.

Rayky’s wartime experience was no less dramatic than Léon’s but would end in tragedy. Her mother, Lambertine Bronckhart, was a member of the Comète Resistance network which helped Allied soldiers and airmen shot down over occupied Belgium to escape and return to Britain.

Lambertine was denounced and arrested by the Gestapo in February 1942. After six months in St Gilles Prison, she was deported and held in concentration camps at Essen, Zweibrücken, Mauthausen and Bergen-Belsen, where she died in April 1945 aged 54.

These painful memories did not prevent Léon and Rayky finding happiness together. They married in England in 1953 and had three children, Léon-Philip, Ingrid and Marion. Léon also has five grand-children: Audrey, Bryan, Sean, Max and William, and one great-grandson, Camilo. Sadly, son Léon-Philip died in 2018, just four years after Rayky passed away.

Parachute jump at 90

Léon retired at 65, but remained very active. When he was 73, he took his first parachute jump, with his 17-year-old grand-daughter Audrey.

“Despite all his time flying, he’d never had to jump out of a plane. When Audrey asked if he wanted to jump with her, he said yes straight away,” recalls her aunt, Marion. Then 17 years later, by which time Léon was 90, he proposed they do it again. “Audrey said, ‘oh yes’,” laughs Marion. “My sister Ingrid and I thought dad must be crazy, but he did it and he was fine afterwards. For him, this type of thing is normal. A few years before he descended on a rope slide from the top of the Atomium.”

Léon told his daughters that he wanted to make another parachute jump – when he was 100 in 2025. Sadly, a recent fall put paid to that ambition and he passed away peacefully.

Marion described her dad as a tough, yet humble, man with a "great, great sense of humour" who made her laugh all the time.

In a message to branch Secretary Andrée Ferrant shortly before her father passed away, Ingrid wrote of how important the Legion had been to her dad. "I know how much my dad cared for this association," she said. "Now he is slowly leaving us and preparing for his last flight to join his 'brothers of the air' and my mother," she added.

An extraordinary man, an extraordinary life. We will remember him.

Léon was awarded 13 medals during his military career:

- Commander's Cross of the Order of Leopold II

- Officer's Cross of the Order of Leopold

- Officer's Cross of the Order of the Crown

- Cross of War with Palm

- Medal of Resistance

- Political Prisoner Cross 1940-1945

- Cross of the Escapees

- 1940-1945 Combatant Volunteer Medal

- War Memorial Medal 1940-1945 (Lion - Crown)

- War Fighting Military Medal 1940-1945

- First Class Military Decoration

- Defence Medal (GB)

- Commemorative 1939-1945 (GB)

Pictures kindly provided by Marion Rubin

Additional interview and update by Dennis Abbott