Douglas Harold Hodson 20/4/33 – 1/2/19 Eulogy by his son, Patrick (slightly edited for this Profile).

"Today, we come together to remember and celebrate the life of Dougie: a loving husband and father, a doting grandfather, and a loyal friend to so many".

Douglas Harold Hodson was born in 1933, in Coventry, not so many miles from Byfield. He was the youngest child of Archie and Olive Hodson with two older siblings Margaret and Anthony.

He did well at school completing his education at King Henry VIII Grammar School in Coventry. Of course, his city experienced the most appalling war damage in the blitz of 1940 when he was seven, and the ability to recover from this and see beyond the immediate difficulty of one’s personal circumstances could be a seemingly insurmountable challenge. But Dougie had broad horizons which were to take him to every corner of the World.

After matriculating, Dougie started his career with Coventry City Council; the building in which he worked overlooked the police training facility. It was clear to him that he would rather be there, and he went with his mother to be interviewed by the Chief Constable. When the Chief Constable asked his mother what she thought of her son joining the police she said she 'was appalled at the idea'.

His independence obviously created a positive impression because he was accepted and joined the force not long after. In his first year he received a Chief Constable’s Commendation for arresting a burglar. He was clearly cast from the Dixon of Dock Green mould and was always fair in his dealings with people. This is perhaps best exemplified by the time he was called out to his parents’ house for a chimney fire. This resulted first in him summonsing his own father and later in his receiving - from his father - a thick ear and the bill to cover the cost of the fine.

National Service follo wed; Dougie was recruited into the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. His first duty was to guard Montgomery’s personal "Grant" El Alamein tank, which had pride of place outside the Guardroom and now sits in a pre-eminent position at the Imperial War Museum. Later Dougie was given spiritual redemption from this arduous task when appointed as the Regimental Padre’s batman, with responsibility for looking after the regimental silver. Clearly identified as someone who could and should go further, he was later commissioned into the Royal Military Police. To the day that he died in February 2019, and despite the ravages of dementia, he could still remember his Service Number.

wed; Dougie was recruited into the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. His first duty was to guard Montgomery’s personal "Grant" El Alamein tank, which had pride of place outside the Guardroom and now sits in a pre-eminent position at the Imperial War Museum. Later Dougie was given spiritual redemption from this arduous task when appointed as the Regimental Padre’s batman, with responsibility for looking after the regimental silver. Clearly identified as someone who could and should go further, he was later commissioned into the Royal Military Police. To the day that he died in February 2019, and despite the ravages of dementia, he could still remember his Service Number.

His children, and grandchildren, consider themselves very lucky to be here today. On being commissioned into the Royal Military Police, Dougie was posted to the Canal Zone in charge of the No. 1 dog detachment in Moascar, near Ismalia at the Suez's Canal's half-way mark. Early on, an army lorry he was travelling in was intentionally rammed by an Egyptian lorry, and whilst Dougie survived, his driver was killed. It is a measure of Dougie’s compassion that as his last duty in the army, he went to London to visit the mother of that driver, Lance Corporal Cooper, to spend time with her and tell her about her son, Edwin.

After National Service Dougie returned to the Coventry City Police. The new duty assigned to him was to drive the squad car, in reality this meant spending most of his days delivering pig swill for his Sergeant who was running a farming business on the side. It was time to look to a future elsewhere!

It was also at this time that he met his first wife Patsy, who had started her nursing career at Gulson Road Hospital. They became engaged and he was recruited to serve in the Uganda Potectorate Police as soon as they were married. For a man of peace who eschewed violence, and would never sanction the death penalty under any circumstances, he shot a large number of game there but insisted that the meat was shared and consumed. He loved his time in Uganda. He was the only person that we know of who physically took fingerprints of an orphaned gorilla, and subsequently maintained correspondence with Dian Fossey on the similarity of print whorls between gorillas and humans. Then, in 1958, the arrival of their first daughter Julie brought immense joy to Patsy and Dougie.

Following Ugandan independence Dougie’s colonial career moved to Fiji. This is where their daughter Rachel and son Patrick were born and enjoyed what was in many ways an idyllic childhood. As much as Dougie and Patsy loved Fiji and the generosity of the people, it was a difficult time for them. In the Fijian CID, Dougie worked very long hours with very little support, and he also had to cover large geographical areas prone to typhoons. As he was now the Aide de Camp to the Governor he was away from home for long periods.

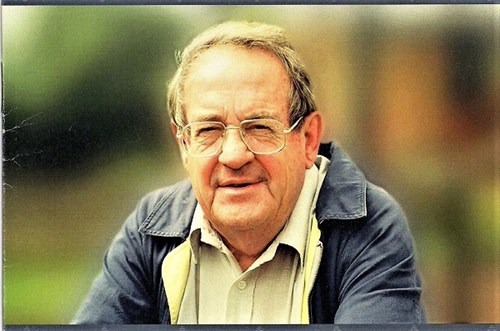

"For us, Julie, Rachel and Patrick and later-on Victoria, he was simply Dad. I often look at his photograph reproduced here as I approach this last year of my own 35 years’ service in the police – there, he was a boy in a policeman’s uniform. He was a young cadet in a bombed out garden, with a beaming smile and large protruding ears, below a hat which is clearly too big for him. Those protruding ears were quite literally an anchor for me as a child, as I clung on to them with a curled up fist."

He was someone who admired academic pursuit and was always keen to see how his children got on. As a little boy, Patrick proudly wore his school cap when the family was on holiday in Coventry. Dougie and Patsy made considerable personal sacrifices to send their children to boarding schools in the UK. It was hard for them to be so far away from their parents at such young ages and Patrick remembers huge excitement when he received letters from his Dad in Fiji, in Dougie's beautiful cursive handwriting. As his children they saw him through the narrow prism of a father who loved them and did his best for them.

Dougie's frequent absences lead Patsy to depression, exacerbated by the lack of professional support in Fiji, which sadly placed considerable strain on their marriage and that eventually came to an end.

With Fiji’s independence, it was time to move again. Dougie was invited to join the Royal Hong Kong Police by Roy Henry, their Commissioner. Fresh leadership was required to stamp-out the systemic corruption in that Force and officers whose integrity was beyond reproach were sorely needed. Dougie was viewed with suspicion by some in Hong Kong, and the ‘Coconut Contingent’ of officers recruited from the South Pacific were not overly welcomed by those who regarded them as a threat.

Dougie did much to dissuade people of their misplaced hostility and over the years became not only welcome, but highly respected. He forged close friendships with many colleagues. To quote one such friend and colleague: ‘he was an inspiring leader and a wonderful example because he never shirked the responsibility of doing what was right’.

Dougie was mischievous and could not abide pomposity. He had a healthy disrespect for authority but was not afraid to speak up when something was wrong. Dougie was also someone who was able to see what police work was about – not performance pledges, surveys and irrelevant bureaucracy, but human beings and service to those in m ost need. He excelled at distilling problems down to how people should be best looked after and he did this with his own officers, as well as the communities he served. He received the Fiji Police medal and displayed his modesty after being awarded the Colonial Police medal erroneously in the U.K.'s New Years Honours List; in declining it, he asserted that they were mutually exclusive. Many lesser men would have simply accepted both.

ost need. He excelled at distilling problems down to how people should be best looked after and he did this with his own officers, as well as the communities he served. He received the Fiji Police medal and displayed his modesty after being awarded the Colonial Police medal erroneously in the U.K.'s New Years Honours List; in declining it, he asserted that they were mutually exclusive. Many lesser men would have simply accepted both.

After Dougie's retirement from the HK Police in 1987 he declared he was going to live gracefully and grow roses. Everyone knew this to be utter nonsense – he wouldn’t have a clue how to grow a rose and his passion was being with people. So after a year as the Director of Northamptonshire Red Cross he embarked on a new adventure in the Bophuthatswana Police.

Dougie had by then met Sally; they were married and embarked on a new life with joy. Their happiness was complete with the arrival of Victoria.

Dougie’s love of the outdoors and for wildlife had remained intact since his Uganda days. His son Patrick can vividly recall being with him on safari – Dougie sniffing various spoor and confidently identifying elephant or kudu. He and Sally had many happy years in Bophuthatswana where they made new and enduring friendships. But with the release of Nelson Mandela, and the ending of the wickedness that was apartheid, it was clear that Bophuthatswana woul d be reabsorbed into the modern Rainbow Nation.

d be reabsorbed into the modern Rainbow Nation.

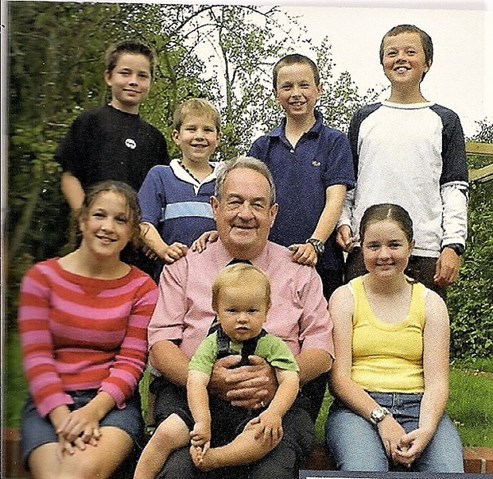

So, Dougie and Sally returned to Byfield, a little village in the middle of England, a world away from Southern Africa. With their cosmopolitan experiences, they both soon fitted seamlessly into village life - and took-up playing lawn bowls in the village's Bowls Club; Sally with significantly greater success than Dougie. As the years passed, more and more grandchildren arrived on the scene. Dougie was clearly devoted to them all and, as his memory started to leave him, the process of looking at photographs to identify which was which and who was studying where, became increasingly important. He never lost interest or the desire to follow the progress of each of them individually. Nor did he lose the desire to fill them with ice cream – and beer as they got older – on crossing the threshold. We all know that this was simply a ruse so that he could indulge himself.

As Dougie's health declined, Sally devoted herself to looking after him and keeping him on the straight and narrow. Not always an easy task!

"Sally deserves the family's heartfelt gratitude for the love and support she gave Dougie, particularly at times when he was perhaps at his most cantankerous. Her dignity and stoicism throughout this time deserves our fulsome praise.

Dougie was always a people first person. He loved talking to people. He walked with Kings as he did when he looked after Prince Charles who made a Royal Visit to Fiji, but equally he never lost the common touch as he stood chatting in Swahili with the East African security guard in his local supermarket in Banbury.

Dougie would always tell his children that their greatest responsibility must always be directed to the generations following us. He loved his children very much. His pride in Julie’s creative talents, Rachel’s academic successes and Victoria’s growth into womanhood and subsequent motherhood were always things he was never shy to tell people about. His unbridled joy at seeing his youngest grandchild, Scarlett running around the house was something to behold.

I hope we can meet this greatest responsibility.

I have his cap with me today and I will pass this on with much love to my youngest child Joe who, because of some genetic idiosyncrasy, always grasped my ear with a curled up fist in exactly the same way I did with Dad".

Not only did Dougie support Byfield's clubs but for most of his time since he and Sally settled here, our Royal British Legion. Until his advancing age precluded it, he was an avid recruiter and after he handed those reins over, he still attended every meeting or event he could.

R.I.P. Dougie Hodson, we will remember you.

Elsewhere amongst these pages, you will find a story about The Battle of Jutland. Dougie's son Patrick, who lives and works in Hong Kong, reminds us that Hong Kong's noonday gun was actually used as a weapon of war in that Battle.