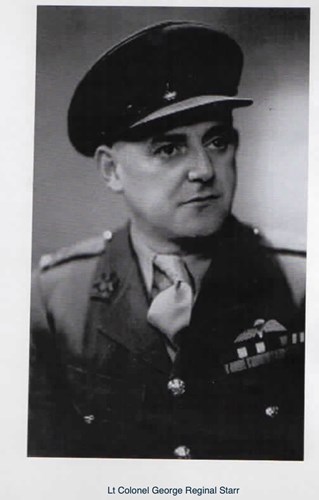

Decorated, daring and dauntless, Lieutenant-Colonel George Starr DSO MC

Branch President (1950-58)

By Dennis Abbott

George Starr is one of the most distinguished – and colourful – figures in the history of the Brussels branch of the Royal British Legion.

Image kindly provided by Alfred Starr

He was also one of the most daring and decorated officers in the Special Operations Executive (SOE), the secret “Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare” created by Winston Churchill “to set Europe ablaze”. Starr (code-name Hilaire) led the “Wheelwright” resistance network in southwest France from November 1942 until the liberation in September 1944. Cells under his command carried out numerous sabotage operations in the build-up to D-Day and crucially delayed the 'Das Reich' SS Panzer division from reaching the Normandy landing beaches before the Allied bridgehead was established.

Starr was born in Kensington, London, on 6 April 1904. His American father Alfred, a bookkeeper for Barnum & Bailey’s Circus, met his mother Ethel when the circus visited England during a European tour with Buffalo Bill Cody. Ethel’s father William built the railway carriages that transported the circus and its animals around the country.

Along with his younger brother John, who would also become an SOE agent (code-named Emile and Bob), Starr was educated at Ardingly College in Sussex. After leaving school at 16, he spent two years working as a miner at Madeley Wood Colliery in Shropshire. “It made a man of me,” he later recalled.

At 18, he enrolled at the Royal School of Mines in Kensington to study mining engineering, but didn’t complete the course. Instead, at 20, Starr moved to Vendôme, Loir-et-Cher, where his father was working, and spent two years learning to speak French at the local lycée. He then returned to Madeley Wood, only to fall out with the mine’s new management.

Keen to stay in the industry, Starr joined Mavor and Coulson, a Glasgow firm manufacturing mining machinery, which sent him to work with their representative in Brussels. The job took him to Poland, Russia, Czechoslovakia, Tunisia and Spain, supervising the installation of mining equipment. During this period he married a French actress but the relationship ended within a year.

In 1934, Starr was loaned to a Spanish company to work at a mine near Barcelona. It was there that he met Pilar Canudas Ristol at a social club dance – she swept him off his feet and they were soon engaged. The couple were married by proxy because Starr was working in North Africa and had to miss the civil ceremony, but he was back in time for their “proper” wedding at St George’s Church in Barcelona on 6 August 1935.

They had to forgo a honeymoon – straight after the ceremony Starr’s firm ordered him back to Brussels. Their marriage was quickly blessed with children, Georgina (born December 1936) and Alfred (July 1938). The family made their way to Catalonia at the end of the Spanish civil war. Sadly, Pilar’s father died the day after they arrived.

Pilar, Georgina and Alfred. Image kindly provided by Charles Glass

During this period, Starr was recruited by MI6, the foreign secret intelligence service, via a contact at the British Embassy. Starr was working in a mine near Liège when the Germans invaded Belgium on 10 May. He hurried back to Brussels and the Embassy provided Pilar and the children with transport to Paris, from where they made their way back to Spain by train.

Escape from Dunkirk

The Embassy staff in Brussels were evacuated, but Starr, who had volunteered for the Army, was given a battledress and ordered to man the fort alone. With the Germans at the gates of the city, he blew up the radio and escaped on a truck with a unit from the Royal Sussex Regiment. Within days he was back in Britain after being evacuated from Dunkirk.

It would be more than four and a half long years before he would see his wife and children again.

Starr was initially attached to the GHQ Liaison Regiment, known as Phantom, which counted the Hollywood actor David Niven among its squadron commanders. Starr was given responsibility for a carrier pigeon loft near St James’s Park in London. The birds took messages to and from France. In April 1942, he was selected for training by SOE and sent to Wanborough Manor, a country house near Guildford, where potential agents – many of them civilians – were put through their paces. More rigorous training followed at Loch Morar in the Scottish Highlands, where Starr learnt how to handle explosives, sail, live off the land and kill with his bare hands. “I’d never been fitter in my life,” he said later. Parachute training at Manchester Ringway followed, with further tests in the New Forest and Cardiff.

Starr was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in July 1942 and in late October he left Glasgow by troopship, bound for Gibraltar, on his fist mission. From the Rock he was taken by felucca – a converted sardine trawler – arriving after a three-day voyage at Port Miou, a deserted inlet on the French coast near Cassis, on 3 November. The vessel carried six other agents including Odette Sansom. Upon landing, Starr was surprised to be pulled ashore by his brother John, who was heading on the same boat back to Gibraltar.

George (right) and his brother John. Image kindly provided by Charles Glass

Arrival in Aquitaine

Starr moved between Cannes, Toulon and Marseille, where he later alleged that Odette twice tried to seduce him. It was planned that he would operate in Lyon but he quickly discovered the city was “blown sky high and everyone was on the run”. Instead he returned to Cannes and then made his way to Agen in Aquitaine. His contact there was Belgian-born printer Maurice Rouneau (code-names Albert and Galles), who took Starr to Castelnau-sur-l’Auvignon, a remote village 40 kilometres away, where Rouneau’s girlfriend Jeanne Robert was school-mistress.

Starr posed as a retired Belgian mining engineer called Serge Watremez (the name of a former class-mate in Vendôme) who had made a fortune in the Congo. Step by step, he began to build up a resistance movement, which the SOE named Wheelwright. London parachuted weapons and explosives to Starr who quickly earned the respect of the local maquis. In the Spring, after weeks of hearing nothing from headquarters, he sent a message via another SOE agent requesting more weapons and a wireless operator.

He received the weapons and Yvonne Cormeau (code-name Annette), a young widow Starr had known in Brussels before the war when she and her husband were members of the same tennis club, was parachuted into Gascony on 22 August 1943 to be his wireless operator and courier. She quickly proved herself a quick-thinking and highly skilled agent, transmitting hundreds of messages without detection. She was an indispensable asset for Starr and some were convinced their close relationship went beyond the purely professional – a view dismissed by her daughter Yvette in an email to the author of this article. “When she and George met up in ‘Wheelwright’, George learned that my father had been killed and that she had left her small daughter with some nuns to risk her life working in a very dangerous environment as a/his radio operator with SOE, for which he was very grateful. So yes, there was a special relationship between them, but not what people assume!”

Yvonne Cormeau, image kindly provided by Yvette Pitt

The Wheelwright network received permission from SOE in December to step up their attacks on the Gestapo and key infrastructure. Starr’s explosives expert Claude Arnault (code-name Néron) successfully put the national gunpowder factory near Toulouse out of action and later blew up a tank and aircraft equipment plant near Lourdes. Starr, meanwhile, was by now in command of a small, polyglot army of French peasants, Spanish guérilillos, German dissidents and refugees from all over Europe. It was dubbed “the Colonel’s Hollywood Brigade”, writes Charles Glass in his book They Fought Alone.

Battle of Castelnau

But Starr faced an enormous setback when the Germans discovered his base in Castelnau and attacked in force on 21 June 1944. Nineteen resistance fighters were killed and the village destroyed. Starr and Cormeau, who was wounded (the dress she was wearing and her blood-stained briefcase are displayed at the Imperial War Museum in London), managed to escape with other survivors, but suffered further losses as they made their way south to join forces with resistance leader Maurice Parisot and the “Armagnac Battalion”.

Starr persuaded SOE to send more ammunition supplies and the battalion successfully engaged units of the Second “Das Reich” SS Panzer division on 2 July, capturing nearly 200 enemy troops including two colonels at L'Isle-Jourdain.

On 21 August, Toulouse fell to the French Forces of the Interior. Starr and Yvonne Cormeau drove into the city to celebrate, but their mood soured later when General Charles de Gaulle, head of the Provisional Government, ordered that they leave France. Starr undiplomatically replied that he did not recognise De Gaulle as his superior and was threatened with arrest. They eventually parted with a brief handshake but, deciding discretion was the better part of valour, Starr and Cormeau left for Paris where they were debriefed by the British Ambassador, Alfred Duff Cooper, before flying back to Farnborough.

Emotional reunion

Starr was questioned by SOE after a fellow agent at Castelnau, Anne-Marie Walters (code-name Colette), accused him of failing to prevent his resistance allies from torturing Gestapo agents and suspected collaborators. A Court of Enquiry was ordered, but in the meantime Starr returned to Paris with SOE F Section chief Colonel Maurice Buckmaster to help locate those who had helped SOE. Starr was given leave for Christmas and had an emotional reunion in Staffordshire with his wife and children who had flown to Britain via Lisbon.

In February 1945, he was ordered to give evidence to the Court of Enquiry, which cleared him of the charges. The transcript of his evidence later disappeared.

The same year Starr was decorated with the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) by George VI, his proud parents accompanying him to the investiture at Buckingham Palace. He had previously received the Military Cross.

Lt Col Starr with his parents outside Buckingham Palace after receiving his DSO from King George VI, image kindly provided by Alfred Starr

With the war almost over, Starr expected to return to civilian life but was instead approached by MP Manny Shinwell, Minster of Fuel and Power in the post-war Labour government, to stay on and help SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) to get the coal mines in the Ruhr operating again. Starr, once again separated from his family, was based near Essen and had responsibility for mine supplies. Yvonne Cormeau was part of his team.

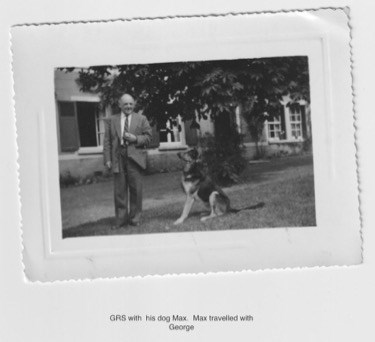

Lt Col George Starr and Yvonne Cormeau at Villa Hugel in Essen with Max the dog, image kindly provided by Yvette Pitt

Back to Brussels

After finally getting demobbed in 1947, “Twinkle” Starr, as he was inevitably nick-named, was asked by his old company to set up Mavor and Coulson (Continentale), which had an office at 65 rue Georges Raeymaekers in Schaerbeek.

Starr, meanwhile, bought a property in Coye-la-Forêt in Oise, France, which became the main family home. “My father ‘commuted’ from there. He had a bedroom in the office in Brussels and later rented a small apartment in the city. He travelled a lot,” recalls Alfred in an email from his home in Sydney.

This period marked the start of Starr’s long association with the Brussels branch of the RBL, which he presided over with panache for eight years.

The stocky, hard-smoking, pugnacious wartime hero was a popular figure in Brussels society, representing the branch at numerous high-profile events. In December 1956 he and Cormeau were honoured together at an official dinner in the city attended by Count Hubert Pierlot, Belgium’s wartime Prime Minister in exile.

After retiring, Starr remained in Coye-la-Forêt. He died in nearby Senlis on 2 September 1980, at the age of 76.

In addition to the DSO and MC, Starr’s decorations included the Legion d’honneur (Officier), Croix de Guerre avec palm, and Medal of Freedom with Silver Palm.

Lt Col George Starr with his dog, Max.

Sources:

Alfred Starr (son of George Starr), email exchanges with Dennis Abbott

Yvette Pitt (daughter of Yvonne Cormeau), email exchanges with Dennis Abbott

Charles Glass, author of They Fought Alone: The True Story of the Starr Brothers, British Secret Agents in Nazi-occupied France (Penguin Press, 2018)

George Starr interview with Geoffrey Lucy, Imperial War Museum (1978):

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80022295

Pilar Canudas Ristol interview with Geoffrey Lucy, Imperial War Museum (1978): https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80022296

History of the Resistance: Exploring Castelnau-sur-l’Auvignon in the Gers (2018): https://www.francetoday.com/learn/history/castelnau-sur-lauvignon-in-the-gers/

Tableau de l’historique des agents infiltrés/exfiltrés en/de France de 1940 à 1945: http://www.plan-sussex-1944.net/francais/pdf/infiltrations_en_france.pdf

Annales des Mines de Belgique/Annalen der Mijnen van Belgie 1950-58